Written by Dan D’Ambrosio at Burlington Free Press, June 4, 2015

Every year, an estimated 3.5 million children die for no reason other than the impacts of poverty.

These children, ages 5 and younger, die from preventable diseases such as pneumonia, dehydration, diarrhea, and systemic infections that could be treated with antibiotics. Ninety-nine percent of them live in poor countries.

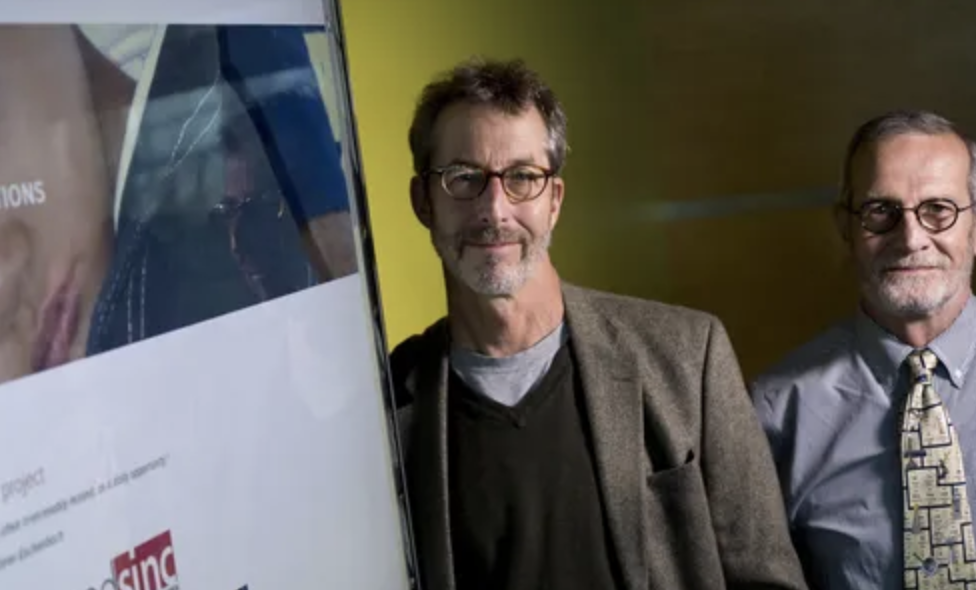

Dr. Barry Finette, founder and CEO of Burlington-based THINKmd, and a pediatrician, has witnessed some of those deaths first-hand. Finette has worked on humanitarian medical missions in countries including Bhutan, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Republic of Congo and Uganda.

Sometimes the death of a child from an untreatable medical condition is inevitable, even here in Burlington, Finette said. Children in Burlington die despite the availability of resources and expertise to help them.

“If you don’t live in a country that has those resources and expertise then you die simply because you’re poor,” he said. “That’s what drives me to do what I’m doing now, to try to bridge that gap.”

Together with his partner, pediatrician Dr. Barry Heath, Finette has developed a smartphone-based medical intelligence platform that allows community health workers without medical training to diagnose and treat sick children with remarkable efficacy. Field tests in the Philippines and Peru have shown these workers reaching the same conclusions as a trained pediatrician more than 80 percent of the time — a rate of effectiveness that matches what doctors are able to achieve among themselves.

“Although the literature is not robust, if you take 100 physicians and have them examine the same patient they agree about 80 percent of the time,” Heath said. “That was our initial goal. I want someone who has no formal medical training to use this device and to have it agree with a pediatrician 80 percent of the time.”

Mission accomplished — so far. Finette leaves this month for further testing in Ecuador.

The worst they ever had

Both Finette and Heath have day jobs. Finette, 58, is a professor of pediatrics, microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of Vermont College of Medicine and director of the Global Health and Humanitarian Opportunity Program. Heath, 64, is a professor of pediatrics, and chief of inpatient and critical care pediatrics at The University of Vermont Children’s Hospital.

The two have known each other for 26 years, crossing paths as young pediatricians and then as co-workers at the University of Vermont Medical Center. About seven years ago, Finette decided on a major diversion from his work at UVM Medical Center as a researcher and in the emergency room critical care unit for children.

“I took a sabbatical,” Finette said. “I wanted to look into global health and humanitarian work.”

Finette got a diploma from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and another diploma in international humanitarian assistance from Fordham University in New York and the United Nations in a program called the Center for International Humanitarian Cooperation.

“So I got some educational background in these areas,” Finette said.

After that, Finette went to work, volunteering overseas for organizations such as Project Hope, which sent him to Panay Island in the Philippines, devastated in 2013 by Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest storm ever recorded on land.

The journey took almost two days, and Finette was seeing patients 20 minutes after he arrived.

“That’s pretty much how you do it,” he said. “You see physical devastation, an area that’s extremely remote, a poor area. You see people working hard to put things back together.”

Although Filipinos are accustomed to typhoons, Finette said Haiyan was different.

“You could see it in their emotions and the effect it had psychologically,” he said. “It was an experience they’ll never forget. The worst that they ever had.”

In the red

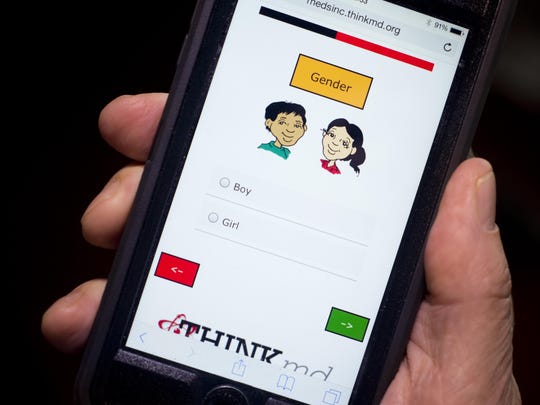

The medical intelligence platform Finette and Heath have developed is called Medsinc. It works by asking a series of questions about a child’s physical condition, focusing on heart rate and respiratory rate, the two vital signs Finette cares about most.

“How fast somebody is breathing — breaths per minute — gives you an idea if the child is breathing faster or slower than normal,” he said. “We use that data and put it in our algorithm and scoring systems to try to gauge respiratory distress.”

Of course there are other ways to gauge respiratory distress. On his smartphone, Finette played one of the training videos available on the Medsinc platform, showing a child in his mother’s arms.

“This is a baby doing head bobbing,” Finette said. “That’s a baby who is in really severe distress. It means they’re working so hard to breathe their head is bobbing back and forth.”

Another simple test uses a form of tape measure to determine if a child is malnourished. The tape measures in colors rather than inches. The health care worker measures the circumference of the child’s upper arm.

“The more malnourished they are, the smaller the upper arm will be,” Finette said. “There’s been a lot of work to determine how malnourished they are, if you’re on that tape in green, yellow, or into red, red being severely malnourished. You put this data into Medsinc.”

The Medsinc questions keep coming. Why is the child coming in? Fever, cough, diarrhea? Does your child have blueness around the mouth, coughing? Vomiting? If they are vomiting, how often? Are they breastfeeding or drinking normally, more than normal, less, or not at all?

“If they cry, do they have tears?” Finette said. “This has to do with dehydration. If you’re really dehydrated you won’t be able to produce tears. The idea is to figure out the simplest questions we can to provide us the best information.”

When Finette first had the idea for Medsinc in 2013, he went to Heath’s office to run the concept by him.

“He said, ‘This is what I’ve been thinking, do you think this would work?'” Heath remembered. “I said, ‘Yes I think this could work and I’ll help you out.'”

Finette was surprised by Heath’s offer to help. He was only looking for an opinion he respected.

“There were a couple of reasons I went to his office,” Finette said. “One is because Barry is going to give me an honest opinion. And his opinion relative to how to assess children who are sick is as good as anybody I know. If I could get it past Barry and his critique of it, then I can get it past anybody.”

One doctor for 60,000 people

The challenge Finette faced as he contemplated making a dent in the overwhelming toll of disease on poor children was primarily a shortage of skilled healthcare professionals.

“In rural areas of the Philippines there was one physician responsible for about 60,000 people that lived in that region,” Finette said. “In Burlington, there’s one doctor for every 300 or 400 people. In general in the United States there’s one physician for every 500 or 600 people.”

There are typically many more community health care workers. Finette couldn’t train 500 new doctors, but he could arm 500 community health care workers with a tool that would make them the next best thing to a doctor.

“So that’s where I came up with this idea of developing this medical intelligence platform anybody can be trained to use,” Finette said. “Asking 20 to 25 questions on the history of the patient, taking some vital signs, some basic physical examination, then pushing a button and saying, ‘This child appears to be in respiratory distress, and it’s this severe. This child is dehydrated and it’s this severe,’ so on and so on.”

Medsinc is perhaps at its most ingenious when it comes to determining heart rate and respiratory rate. Finette found that many health care workers were ill-equipped to accurately determine those vital signs. Many of the workers, for example, don’t have watches.

Finette brought up a screen on his smartphone with a large red dot.

“We built this thing you just tap every time you feel a heartbeat, and it tells you what the heart rate is,” he said. “We do that for heart rate and respiratory rate. Every time a baby breathes you just tap it and it calculates the rate.”

The power of economics

Finette and Heath formed THINKmd last August after the University of Vermont passed on developing Medsinc. As Finette’s employer, UVM had first dibs on Medsinc. After the institution declined to pursue it, Finette secured the intellectual property for THINKmd. He decided on a for-profit company rather than a nonprofit so he wouldn’t be at the mercy of granting agencies and organizations.

THINKmd is a Vermont benefit corporation, meaning its humanitarian mission is built into its DNA, but that the company is out to make a profit.

“I want to build something I can make sustainable,” Finette said. “The best way is to use the power of economics to do that. I have a product I can sell. And even in the poorest countries people don’t want to be given things. They just want opportunities.”

Finette and Heath are trying to raise an initial round of $250,000 in seed funding from investors. They’re about halfway home. That’s where new Chief Operating Officer Nick Donowitz comes in.

Donowitz graduated from Duke University in 2010 with an MBA and a master’s degree in environmental management. Since graduation he’s been working off and on for Mars, Inc., of M&M’s and Snickers fame, helping the company on a project in Indonesia to help the cocoa communities Mars buys from.

“Most of the folks are very poor and smallholders on an average 2.5 hectares of land,” Donowitz said. “My role was working on how to train but also to deploy technology developed by Mars on soil management and water quality.”

When Donowitz learned of Finette and Medsinc he knew immediately he wanted to be involved. For one thing it would keep him in Vermont where he moved to three years ago.

“My goal has always been to plug in locally and start great companies in Vermont,” Donowitz said. “Right now Barry is doing an incredible job with a full-time job at the university of getting his product developed in beta phase to prove the concept, prove the demand.”

Donowitz expects a product launch for Medsinc in early 2016.

“Although this application is ordained to have impact in resource-poor areas of the world without access to quality health care or health care at all, there’s application in middle and upper income countries for a similar version of the platform,” Donowitz said. “This is very much a global opportunity we’re chasing.”

In countries like the United States, Finette explained, Medsinc could be used to determine if a sick child really needs to go to the emergency department, or for triage in doctors’ offices.

Doctor in a box

John Rosenblum, founder of Green Mountain Logic, a health science software company eventually sold to Oracle, volunteers as a strategic advisor to THINKmd. Rosenblum sees a clear use for Medsinc in developed as well as developing nations.

“When kids spend three hours waiting to be treated for a simple cough we think there’s lots of use for Medsinc in the hands of lower level medical personnel under the supervision of doctors,” Rosenblum said. “They can process that child much faster, as well as parents being able to check and see if their kids are sick enough to take to the ER, theoretically.”

Rosenblum hopes Medsinc will make a long-held dream of his come true: to “put a doctor in a box.”

“That was my dream and the reason I got involved with software was because I wanted to participate in creating artificial intelligence software that would behave as a doctor,” Rosenblum said. “Thirty years later we’re finally doing it.”

Like Rosenblum and Donowitz, THINKmd and Medsinc is attracting interest and offers to help from people and organizations around the world. Goodwin Procter LLP in Boston, one of the leading intellectual property law firms in the world, is helping THINKmd pro bono.

“It’s an incredible opportunity,” Nick Donowitz said. “Goodwin Procter will support us with legal fees for an indefinite amount of time, advising us on the right intellectual property strategy. On that we are well covered.”

Rosenblum said the United Nations, non-governmental organizations, and the ministries of health in several countries were “all incredibly excited to have an application like this.”

“We’re not trying to replace doctors,” he said. “We’re simply handing these to a preexisting workforce of health care volunteers who are already in place but don’t have the capacity to assess and treat sick children.”

For Barry Finette, the global vision for Medsinc begins where the need is greatest.

“This sounds a little sappy, but that’s the reason we’re doing this,” Barry Heath said. “Yes, we want to provide appropriate health care to children who need it.”